Icaro y otras mitologías Esteban Schimpf

Esteban Schimpf’s body of work is concerned with big questions: what is the place of art in

society, what constitutes an image, can an artwork be completely abstract, can art escape

narrative and ultimately, what is art? When Schimpf tackles the biggest of these questions

“What is art?” his response is like a man wrestling with his own faith “My response was

simple, still lifes, nudes, and landscapes.” This is a mythology intended to raise eyebrows

with suspicion. We should not believe him in his conclusion, yet he believes it himself.

In another instance of reflection he admits ” I guess that I’m a liar. Never trust a man that isn’t!”

It is this statement that is mode of entry into the work, Schimpf makes images that reify the

mental disposition in a contemporary world of disillusionment, connectivity, digital isolation

and radical layering of the self. Schimpf’s photographs document excess, subversion into the

ubiquity of screens and digital streams. Most poignantly the derailment of the American

Dream. In a world flooded with images we identify ourselves as much with the reflection in

the mirror as the “selfie” posted on social media. Yet we have very little physical attachment

to others, even when we are with other people we are often staring into a screen. This condition

of the radically fractured self is also universal, it is the stuff of mythology. In Walt Whitman’s

often quoted “Song of myself” he states :

The past and present wilt—I have fill’d them, emptied them. And proceed to fill my next fold

of the future.

Listener up there! what have you to confide to me?

Look in my face while I snuff the sidle of evening, (Talk honestly, no one else hears you, and I

stay only a minute longer.)

Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes.)

Schimpf was born into a radically fractured family in Colombia and was adopted into a naturalized

American family. For him the American Dream was indeed a promise that could never

be kept. An early work of Schimpf was a manifesto that he co-authored with artist Daniel

Keller titled “The Defenestrationist Manifesto” .

The work is an absurdist call for throwing things out of windows and draws as a source the canonical work of Yves Klein “leaping into

the void” where the artist throws himself in full flight out of the window. This very early student

work links to the title of current exhibition, Icarus also seeks to fly but like Klein we

know he is bound to fall. The lasting power of the Icarus myth is that we can relate to him not

that we imagine being him but that we share his desires. It is his internal trauma that we

relate to not his physical fall.

In this recent body of work Schimpf also focuses on the internal trauma of doubling and repetition.

These are two aspects of the uncanny, the double is the impossible replicate, repetition

is the hallmark of trauma turned into neurosis (seen in obsessions, compulsions and

addictions). In the photograph Castor and Pollux, 2016 the double is literally the silhouette

shadow of the main portrait. The silhouette appears as if cut out from a sky blue and white

patterned sheet, perhaps the same pattern of a composition notebook. On top of the flat silhouette

and in juxtaposition to it are a yellow lemon turned upright and a dead bird turned

on its side (perhaps stuffed). The portrait that is doubled is a man who although has the features

of an African American a black person, has been covered in pink child-safe non-toxic

tempera paint. The brush-strokes are still visible. The deepest layers of the picture (or perhaps

the one most in the forefront) are a black and white photograph of bananas and flowers.

The figure-ground relationship is also shattered in that we are not able to distinguish

what is in front and what is overlapping. The myth of Castor and Pollux is one of twins who

meet a violent end, a metaphorical fall.

Falling is a repeated theme of the work, in one installation in the exhibition a mirrored photograph

(an identical but inverted print) appears fallen onto the floor as if off the wall. In another

image a female figure lies on a white bench her head and hair falling to the ground. This is

the repetition of the fall of man, it is not a dystopian vision of resignation. Here Schimpf’s

work performs a Sisyphean task of pushing the boulder up the hill only to have it roll down

again, but repeating to strive, to climb in the face of the fall.

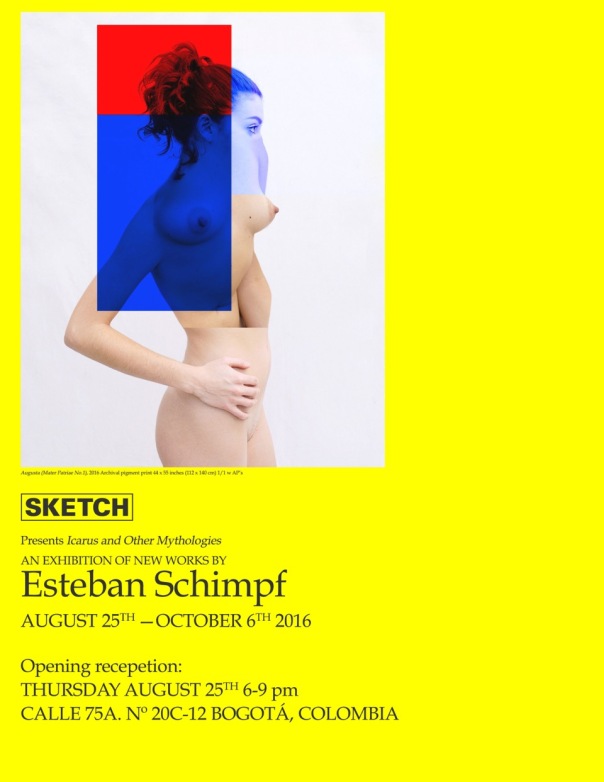

Like his clear paternal influence, the Los Angeles based artist John Baldessari, Schimpf was

trained as an abstract painter. He later came to portrait photography but brought with him

the sensibility of painting. His work is formally composed like the mid-century modern modernist

non-objective geometric painters chief among them, Piet Mondrian. Unlike Baldessari

who’s work relies on irony, humor, and transforming text into image, Schimpf’s work draws attention

to the reverence of life boiled down to its most essential (flour used for baking bread)

and the joy of looking at the human figure. The figure was long abandoned in the conceptual

lineage that Schimpf clearly rejects. He does not follow the modernist desire for the new and

innovation, the goal of avant-garde and neo-avant-garde to break with art history. Instead he

aligns himself with the history of the specific mediums of painting and photography. If photography

was historically a form of documentation of reality (a claim rejected by the

post-modernist structuralists) he reclaims this role. In some of the most moving work, the

photographic portraits capture the act of the artist covering his subject in baking flour, essentially

a performance we are only given privilege to by virtue of his photographic document.

One image captures a nude female figure in a moment where she flings her head

downward throwing the white powder off of her body and face, and transforming from a

white stature to an African American black figure .

The clearest act of layering is in the way the faces are pierced through. The figures are never

in a space in the round, unlike cubism which attempted to capture many angels of the same

object in one image, Schimpf captures the flatness of how we see images today in a digital

word. The figures are always on a flat background with his layering emphasizing the flatness.

In a world where our identity is as much a projection of ourselves as a physical embodiment,

the portraits capture the loss of physical closeness but also the desire to be part of something

greater than ourselves.♦

-Justin Polera

Berlin, Germany